Bedtime has historically been a battle for our family. Kids have this impressive ability to fall asleep when you want them awake and vigorously stay awake when you want them to sleep. To combat the insanity, we read a few books every night before bed. There is a great series of books for young children called “The Magic Tree House”. The series follows two children (Jack and Annie) who transport to other times and places for some mystery or adventure.

While reading one of these books I stumbled upon an interesting passage. The children’s friend, Morgan Le Fay, is trapped someplace in time and space and to find her they need to locate four items. They have already found two (a Moonstone and a Mango). Here is the passage that caught my attention:

“Hey Guess what?” said Jack. “Moonstone and mango start with the letter M. Just like Morgan.” “ You’re right,” said Annie. “I bet all four things start with an M,” said Jack.

I immediately thought, I wonder if that is a statistically valid proposition?. The rest of this blog post contains the plan and execution to rigorously validate this as a reasonable hypothesis.

The Plan

In order to verify the assertion Jack makes, we need to attempt to determine the probability that you would have a friend and then happen upon two items that all start with the same letter assuming you found these things at random.

For example, if we have 1,000 parallel universes (or 100,000) and the Jack’s and Annie’s of these worlds made random friends and found random items, in how many universes would all of these items start with the same letter?

This is our null hypothesis, discussed in detail in my previous post. If we find the likelihood of our observation under the null hypothesis is less than our accepted criteria of 0.05, we’ll have grounds for rejecting it in favor of an alternate hypothesis.

What does random mean in this context? The universes we use for our simulation should behave much like our own: they should have the same distribution of possible friend names and things as we have in our universe.

One way to accomplish this is to do the following:

- Buy two urns

- Wander around randomly

- For every person you come up to that you could be friends with, write their name down and put it in the first urn.

- For every item that you could pick up, write it down and put it in the second urn.

Then you have an empirical probability distribution of possible friends and possible things and you can start to simulate universes.

To do the simulation, you would construct a spreadsheet with one row per universe. You would then pull a friend name out of the first urn, write it down under the row for universe 1 in your spreadsheet, and put it back in the urn. Subsequently you’d draw the name of an item out of the second urn, write that down, put it back, and repeat so you have drawn and replaced 2 items.

Here is a possible outcome:

To figure out if the hypothesis that Jack makes is feasible, you could do this 1000 times, making note of the times when all of your draws have the same letter. If that number is smaller than our p-value (also discussed in my last post), you are well on your way to rejecting the null hypothesis.

To figure out if the hypothesis that Jack makes is feasible, you could do this 1000 times, making note of the times when all of your draws have the same letter. If that number is smaller than our p-value (also discussed in my last post), you are well on your way to rejecting the null hypothesis.

The Problem: Filling Urns

The one hitch in our plan is that filling those urns will take way more time than it’s worth. (Lets be honest, this has already taken more time than its worth). Instead of wandering around in the world to fill the buckets, what if we pulled names of people and things from the written world?

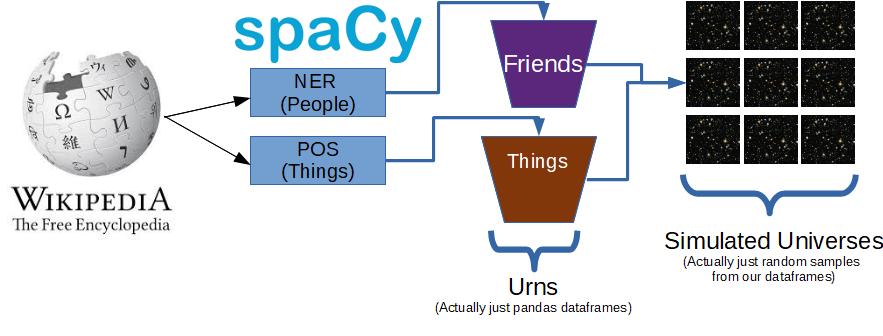

One approach would be to scrape Wikipedia for every childrens author, process the text through an NLP pipeline, and use entity extraction and part of speech tagging to find people and things.

While it will certainly reduce the amount of time until the end of this blog post, it comes at the price of having to make several assumptions. Namely, you have to assume that the distribution of people names in the Wikipedia articles we are scraping is similar to the names of people in the real world who you could be friends with (in other words, we have to assume you are quite friendly)… Additionally, not every noun is something you could pick up (can you pick up the internet?).

With these caveats noted, we’ll live with our simplified assumptions and press on…

So our final approach will be something like this:

The Code

First things first, lets get to web scraping (note, if you’d rather just look at the jupyter notebook with all the code in one place, feel free to pull it from my git repo). One possible (and irresponsible) way to do this is to simply point python’s request library at a Wikipedia URL and parse the output with beautiful soup. This is taxing on the website and could result in any number of things including the web host blocking your IP address.

Instead, its best to see if the site has an API that can be used to pull content.

Wikipedia, because it is awesome, has a great and full featured api. Even better, plenty of people have provided wrappers for the API so you don’t have to manage and format your API requests. One that I have found useful (but hasn’t been updated in a while) is here).

Scraping

Lets import what we’ll need, and search Wikipedia for ‘Childrens Author’

import sys

sys.path.append("C:/Users/mj514/Documents/magicTreeHouseSimulation")import wikipedia # A suprisingly satisfying import statement

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

result = wikipedia.search('Childrens Author')

result## ["Children's literature", 'Alicia Previn', 'Sam Angus (writer)', "Alvin Schwartz (children's author)", 'Renee Ahdieh', "Al Perkins (children's author)", "Douglas Evans (children's author)", "David Elliott (children's author)", 'Author! Author! (film)', "Ruth White (children's author)"]We could use the Childrens Literature page as a jumping off point, lets see what’s in there:

lit = wikipedia.page("Children's literature")

lit.links[1:15]## ['ALA Editions', 'A Book of Giants', 'A Little Pretty Pocket-Book', 'Abanindranath Tagore', 'Acronym and initialism', 'Adventure book', 'Adventurer', 'Africa', 'African American', 'After the First Death', 'Alan Garner', 'Aleksandr Afanasyev', 'Alex Rider', 'Alexander Belyayev']print(len(lit.links))## 702are some random links, but many of the links appear to be to childrens authors or childrens books. We’ll walk through each of these links, grab the page from Wikipedia, and store the contents:

wikipedia.set_rate_limiting(True) # pause between each request so you don't overload the server

bunchOfPages = []

exceptionCount = 0

for p in lit.links:

try:

bunchOfPages.append(wikipedia.page(p).content)

except: #Excepting everything is poor practice, and can get you into trouble, so don't do it

exceptionCount+=1(Warning: this takes about 20 minutes)

We’ll dump this collection of pages as json so we don’t have to pull it every time we want to work with childrens authors’ Wikipedia web pages:

import json

with open('childrensAuthorContent.json', 'w') as outfile:

json.dump(bunchOfPages, outfile)Load it back in and so we can prepare for NLP magic

with open('childrensAuthorContent.json', 'w') as infile:

loaded = json.load(infile)NLPing

Now that we have a bunch of text, we need to find a way to grab the people and the things. Spacy has an excellent, well documented, clean API that will give us everything we need to extract the interesting text.

import spacy

import json

from collections import Counter

import pandas as pd

import numpy as np

from spacy.pipeline import Pipe # Allows for parralelization

import itertools

nlp = spacy.load('C:/Users/mj514/Anaconda3/lib/site-packages/en_core_web_lg/en_core_web_lg-2.0.0') Now we’ll use the pipe module to iterate through each of the texts in our json (which is now just a dict) and apply the SpaCy NLP model in parallel . For each of the parsed documents, we’ll grab all of the nouns (which are things, but sadly not always things you can pick up1) and all of the entities of type = person.

nounLists = []

peopleLists = []

for doc in nlp.pipe(loaded, n_threads=16, batch_size=1000):

nounLists.append([tok.lemma_.lower() for tok in doc if tok.tag_ in ['NN','NNS']]) # things

peopleLists.append([ent.merge().text.lower() for ent in doc.ents if ent.label_ == 'PERSON']) # people namesThe output of this is a list of lists. In order to create our various flavor of urns we need to collapse this nested structure into one list using itertools. I found this a rather dirty, if anyone has tips on how to avoid needing to collapse the list let me know in the comments…

#Apparently this is the fastest way to flatten a list of lists. https://stackoverflow.com/questions/952914/how-to-make-a-flat-list-out-of-list-of-lists

nounList = list(itertools.chain.from_iterable(nounLists))

peopleList = sum(peopleLists,[])Because of our biased sample (seeded the search with the childrens author page), some of the words we’ve extracted might be skewed towards the topic of childrens books. Lets take a look at the top ten most popular nouns in our scraping exercise:

count = Counter(nounList) #use counter to get word frequency

series = pd.Series(count, name='count') #Turn it into a series so we can sort it

stopList = list(series.sort_values(ascending=False).head(10).index)

print(stopList)

# ['book', 'child', 'year', 'story', 'work', 'time', '–', '=', 'century', 'series']Book, child, story and series are all associated with the theme we scraped (childrens authors). Additionally SpaCy picked up some words which are clearly not nouns (-, =). We can safely remove these words from the list, and because they are the most popular words, removing them will have an outsized effect on the answer.

Conventional wisdom suggests that following this process of removing ‘stop words’ (words like ‘the’, ‘a’, ‘it’, pronouns, etc…) will improve the outcome of your NLP exercise because these words don’t add much meaning but instead adding to the noise.

It turns out that stop words can actually add context to a sentence and removing them can often have negative effects on the outcome of your model. Think about the following sentences:

He threw the toy to the dog

Threw toy dog

As you can see, removing stop words has completely changed the meaning of the sentence… In the first sentence the dog is real, the second sentence the dog is a toy. You should carefully consider how you preprocess data (the same can be said for lemmatizing and removing capitalization and numbers). Instead of just following rules of thumb, experiment with your preprocessing steps.

We’ll go ahead and remove our stop words, as I’m fairly confident they won’t improve the simulation (we could probably remove more…)

stoppedNouns = [word for word in nounList if word not in stopList]

print(f"before stopping: {len(nounList)}, after: {len(stoppedNouns)}")

# before stopping: 477525, after: 435139Lets now stuff these into a pandas DataFrame which will give us some of the functions we need to continue to quickly clean and perform the simulation (make our urn):

thingsUrn = pd.DataFrame({'thing': stoppedNouns})

peopleUrn = pd.DataFrame({'name': peopleList})

thingsUrn.head()

# idx thing

# 0 author

# 1 teddy

# 2 bear

# 3 poem

# 4 writerInspecting the data this point reveals that we have several non-word and non-English entities in our urns. We’ll assume that we can’t pick up punctuation (so we’ll remove it) and we’ll assume that we want to limit our evaluation to only the 26 letters in the English alphabet.

This rather ugly code is what I managed to put together to make this happen2. If anyone has a way I could clean this up, feel free to let me know.

thingsUrn = thingsUrn[~(thingsUrn.thing.str.replace('/p{P}+','',regex = True).str.contains('[^a-zA-Z]', regex = True))]

peopleUrn = peopleUrn[~(peopleUrn.name.str.replace('/p{P}+','',regex = True).str.contains('[^a-zA-Z]', regex = True))]We’ve scavenged the internet to fill our urns with people and things we need for our overkill simulation. We fainally have everything in place to execute our master plan.

Monte Carlo Simulation

Before watching some of David Robinson’s excellent videos on ‘tidy simulation’, I would normally do the simulations using a for loop:

#for i in range(1:numberOfSimulations):

#draw a person

#draw a thing

#draw another thing

#write all that stuff down in a list or something

#return the listTo me, this is a very intuitive way to code the solution because it follows what you might actually do to solve this problem as a human:

1000 Times…

This isn’t very fast, and it certainly isn’t compact. Turns out you can do the same with a DataFrame, but the paradigm is a little different. Instead of drawing from all three urns each iteration, you draw everything you need from each urn in one shot.

If you want to do 1000 simulations, you draw 1000 names, then 1000 things, then 1000 more things, and paste all the results together in the end.

Pandas sample method will facilitate the drawing:

numSamples = 1000000

sampledPeople = peopleDF.sample(n= numSamples, replace = True).reset_index(drop=True)

sampledThings = thingsDF.sample(n = numSamples, replace = True,).rename(columns ={'thing':'thing1'}).reset_index(drop=True)

sampledThingsAgain = thingsDF.sample(n = numSamples, replace = True).rename(columns ={'thing':'thing2'}).reset_index(drop=True)

fullSamples = pd.concat([sampledPeople,sampledThings,sampledThingsAgain], axis = 1)Lets peak at our resulting universes:

fullSamples.head(5)

# idx name thing1 thing2

# 0 potter ice tale

# 1 penguin textbook part

# 2 premchand failure forerunner

# 3 twain variety school

# 4 jack website episcopumTo calculate our p-value, we need to count the number of times all three draws have the same first letter and divide that by the total number of simulations performed. The first few lines just extract the first letter from all the names, the last line calculates the ratio outlined above:

fullSamples['first_name'] = fullSamples.name.str[:1].str.lower() #grab the first letter and lower it

fullSamples['first_thing1'] = fullSamples.thing1.str[:1].str.lower()

fullSamples['first_thing2'] = fullSamples.thing2.str[:1].str.lower()

fullSamples['isMagicMatch'] = ((fullSamples.first_name == fullSamples.first_thing1) & (fullSamples.first_name == fullSamples.first_thing2))

np.mean(fullSamples.isMagicMatch)*100

# 0.0039 = 0.39%This result says that under the null hypothesis (the children found the items and made a friend at random), the likelihood of the observation (friends name and first two items start with the same letter) is only 0.39%, which is clearly smaller than our present (5%) and proposed (0.5%) criteria for rejecting the null hypothesis.

In other words we can statistically conclude that something other than random chance is influencing the distribution of things being collected in our childrens story. An alternate hypothesis should be considered.

This doesn’t necissarily mean that the most likely hypothesis is that all 4 of the items will start with the same letter (can you think of a way to use our simulation to assess the probability of that hypothesis?), but it suggests that Jack’s suspicion about how things have turned out so far is on point.

Here is a sampling of our simulations that matched our observed outcome:

fullSamples[fullSamples.isMagicMatch].head()

# idx name thing1 thing2

# 526 penguin party person

# 1367 page production protagonist

# 1374 clay chorister capacity

# 1669 pinocchio printing principle

# 1773 elementary education edSpolier Alert: If you read the next few books in the series, you’ll find that Jack was completely justified in his hypothesis, the next two items were Mammoth Bone and Mouse.

If you made it this far I hope you enjoyed reading the blog as much as I enjoy writing it. For the next post, I plan on moving back into deep learning by showing you how to build a bird sound classifier using deep convolutional Neural Networks and image recognition.

- I tried for a while to figure out how to limit it to just things you can pick up. For example, could we use the dependency parse and identify objects which are acted on by people. In the end I decided to take any noun, but if you can come up with a better way, let me know in the comments! [return]

- One thing to note, you could do these sorts of operations on the list before making it a DataFrame, or element by element by using .apply(). Both of theses methods are slower than the str.replace and str.contains method because the latter methods are vectorized. [return]